Black and Indian: What 18,100 Searches Can’t Tell You About Us

- Jonah Batambuze

- Aug 11, 2025

- 7 min read

Updated: Aug 13, 2025

Every month, 18,100 people search ‘Black and Indian’ — and find less than they deserve

Search Bar

A student with twelve tabs open, the cursor blinking in a half-finished sentence.

A mother watching the blue glow of her phone, knowing the next notification could alter the future — and her standing with family back home.

Someone tracing the thread of the latest diaspora wars split along racial lines, the light of their phone flashing across tired eyes.

They don’t know each other, but this week they typed the same thing:

Black and Indian.

Eighteen thousand, one hundred times a month in the United States alone — as if a small country gathered in the dark, the air thick with the hum of questions no one can quite name.

For them, it might be a breadcrumb. For me, it’s a map worn into the soles of my family’s feet.

I searched those three words once, too — in the early days of falling for Swetha, when I was studying abroad more than twenty years ago. What I found was far less than what you’d see today. No stories of Kamala Harris claiming both her identities, no scandals of brothers pretending at Blackness, no viral weddings where Afrobeats dissolve into Bollywood ballads.

Just the cold light of a blank search result, where centuries had been scraped clean but the outline of their absence still pressed into the frame.

No ocean winds to push you toward a shore.

No trade routes to tell you where the spices came from.

No music in a tongue you didn’t yet know you loved.

Only the quiet hum of a world that had been there all along, waiting in the living tongue of a people search engines could never speak — not in Swahili, Gujarati, or the saltwater Hindi of the coast.

Origins: Black and Indian Foundations

I was born into a story that stretches across the Indian Ocean.

On my father’s side: Musoga, Ugandan, connected to East African coastlines.

On my mother’s side: Mugandan royalty — her grandfather, Serwano Kulubya, once engulfed in a land dispute with Amar Singh, an Indian resident in Uganda.

Long before passports and ports of entry, there were dhows along the Swahili coast, carrying cloves, coconuts, grief, and the possibility of return. Africans lived in Gujarat and Karnataka for over a thousand years — Siddis whose stories did not end in captivity. Indian traders settled in East Africa until the shoreline felt like home.

This is what “Black and Indian” means to me — not a label, but a tide. It moves forward and back, braiding histories in ways that resist the neatness of origin stories.

These aren’t footnotes; they’re the foundation. And without care, they risk being reduced to a hashtag or a novelty. That’s why I tell them not just as heritage, but as infrastructure — scaffolding for solidarity.

The Misunderstandings

When people hear “Black and Indian,” the assumptions usually fall into two boxes:

Dating or fetishization — as if our presence together is always romantic and always exoticised — a stereotype I’ve explored in more depth in this Psychology Today interview on Black and South Asian relationships.

Binary identity — as if you’re either “Black” or “Indian” but never allowed to be both at once.

These snap judgements flatten entire histories into surface readings. They miss the fact that identity is rarely a single origin story; it’s a constellation. What looks like contradiction is often the most honest reflection of our past.

It’s 1:32 a.m. I check my Instagram DMs one last time before sleep.

“I’m single. But I want to marry African girl in future. Just I don’t know girl.”

I sigh. I don’t have the capacity, nor has the time come for us to take over the online dating world.

“Is it true that Indian men aren’t attracted to Black women?”

My pulse quickens. I know the statistics about who gets swiped left the most. But seeing that curiosity in a stranger’s question still lands heavy when I know the answer is, more often than not, yes.

Google’s autocomplete isn’t much different:

Black and Indian person.

Black and Indian kids.

Black and Indian baby.

Black and Indian couples.

Black and Indian celebrities.

If you gathered every one of those searchers in a stadium — 18,100 seats filled — it would look like a country of its own. And in the low hum of the crowd, you’d hear questions that have been asked for centuries: Who are you to each other? What does it mean to belong together?

The truth is, those questions can’t be answered by a search engine. They live in kitchens, marketplaces, songs, and hands passing food across a table — the places where Black and South Asian solidarity has always been built.

From Black and Indian → Black × South Asian Solidarity

I remember being on the What Is This Behavior podcast when they asked about the name “BlindianProject” — how I landed on it, and whether it might alienate some people.

The truth is, the name came from love. The love between a Black man and an Indian woman. My love with Swetha. A relationship that began as two people trying to understand each other’s families and worlds, and grew into a movement that holds space for broader Black × Brown solidarity.

The messages in my inbox still remind me how that doorway is read. A Pakistani woman married to a Jamaican man once wrote: “I wish the BlindianProject was more inclusive, as my experiences mirror the Black and Indian stories on your platform.” She had read the work, recognized herself in it — but the name created a kind of distance.

A Sri Lankan man married to a Kenyan woman told a similar story.

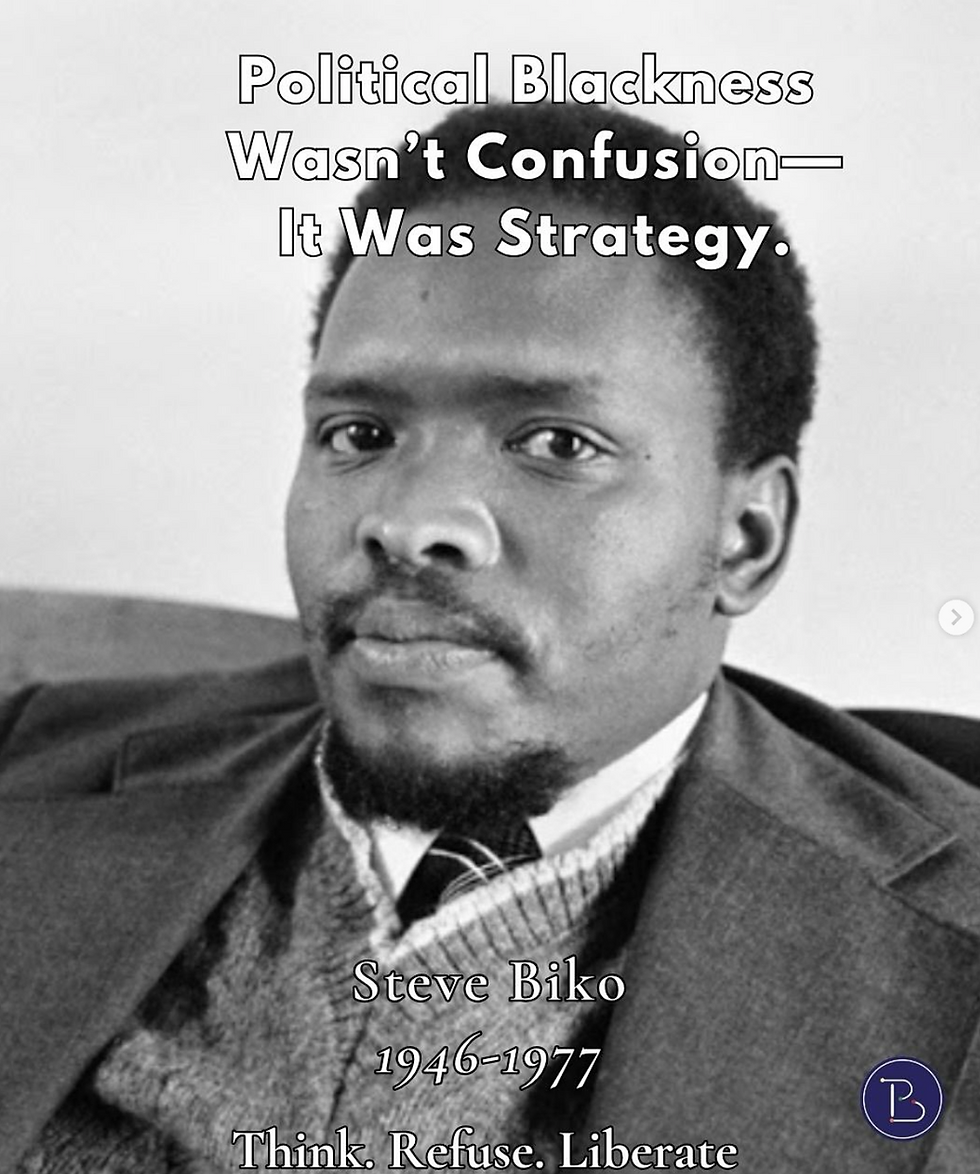

It’s not lost on me that “Black” can mean both race and political consciousness — the kind Steve Biko spoke of in South Africa. And that “Indian” might speak not to one nationality, but to the whole subcontinent before colonizers drew borders, dividing people who shared mother tongues and religions.

What’s in a name, anyway? We don’t interrogate Nike or Ralph Lauren every time we wear them. But with BlindianProject, the name was always the doorway — and the work was always to invite people deeper.

The deeper work has always been moving from identity to solidarity.

That means telling stories about South African Indians standing alongside Black South Africans during apartheid’s fall.

Ugandan Asians who supported African independence movements. Afro-Asian political alliances in the Global South — from Bandung in 1955 to street-level collaborations in music, sport, and cinema.

It also means acknowledging where solidarity has failed — where anti-Blackness, caste, and colourism have driven wedges between our communities. The BlindianProject lives in that tension, refusing easy narratives.

The term “Black and Asian” enters here, too — not just for search engines, but because solidarity demands a wider lens. We are part of a global story that exceeds any two words.

The BlindianProject as Living Archive

I built the BlindianProject because I wanted something that could outlive a news cycle. A legacy that could outlive my physical presence on this earth.

I wanted a space that could help us learn the richness of our cultures — the parts masked by the educational system, still accessible even in a future where public broadcasting and independent media have been hollowed out.

It’s a living archive — evolving, participatory, global. A place where memory is made through conversation, where stories are carried forward, not stored away.

Flagship projects like The Hands of Gods — a film and installation exploring left-handedness as cultural resistance — BlindianProject Histories, which profiles overlooked figures in Black × Brown solidarity, and interactive installations have turned this into more than a platform. It’s a space for encounter — between strangers, between generations, between histories.

Here, “Black and Indian” is not a boundary. It’s an opening.

It’s where you might find intergenerational conversations with elders holding the keys to ancestral technologies not written down in any book — or a New Delhi millennial learning the latest Afro-dance move while trying to make space for Africans in India.

We often work with academics who have dedicated their lives to unearthing our cultures’ hidden stories. But our work keeps the messages accessible — not written like white papers trying to impress other academics, but in language that can live in the mouths of our communities.

The Invitation

This work has always been collective. I’m asking you to add to it.

In 2025, histories of our diverse societal contributions are being erased in real time before our eyes, while resources are diverted to whitewashed narratives. The only antidote is to keep telling our own stories, in our own words, while we still can.

If you carry a Black × South Asian story — from your family, your neighbourhood, your archives — share it. Send a photograph. Record a voice note. Offer a memory that could live beyond you.

You can contribute via [Substack link], email me directly, or send a DM.

Every voice, every artifact strengthens the archive.

Because if you didn’t know, now you do — and now you can pass it on.

Jonah Batambuze is a, Ugandan-American interdisciplinary artist and founder of the BlindianProject, a global platform remixing Black x Brown identity through art, history, and storytelling. His work moves across installation, film, writing, and education—challenging systems of erasure while building new cultural blueprints.

Batambuze speaks and facilitates internationally on topics including Black South Asian solidarity, caste and colonial legacies, diasporic memory, and cultural resistance.

For speaking engagements, workshops, or media inquiries, contact: jonah@blindian-project.com or visit jonahbatambuze.com/speaking

Comments